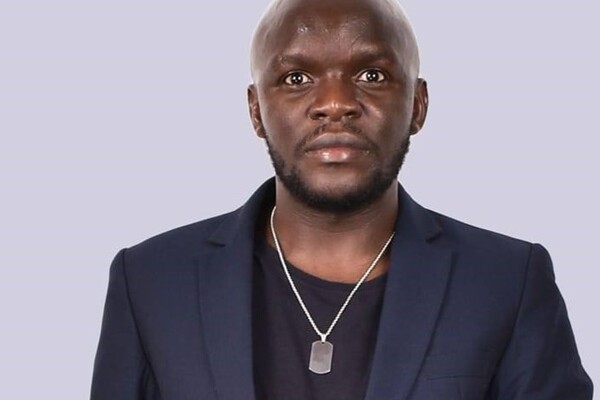

"Have you been to Nairobi?" Brian Malika beams down the Zoom call, excited about heading out into the bustling city later that evening. It's Friday, and Kenyans like to party at the end of a busy week, he says. Malika’s cooking dinner while he talks (it's chicken stew today) and explains that most days, he eats just one meal - a habit that lingers from his days without a steady income and one that is common across Kenya.

Malika doesn't have a typical workday. When his workload is heavy, he gets up at five in the morning and works until late in his home office, but today, he rode his bicycle in the woods after getting up at two in the afternoon. It's one of the perks of being a freelance writer with regular publications in national outlets. It's also why he was late for this interview.

But life wasn't always like that. Before gaining traction as a writer, Malika worked on social issues. He advocated for people with disabilities during a fellowship in the US at the Indiana Institute and, before that, volunteered as a Youth Policy Advisor with the British Council in Kenya for nearly a year and a half. Paired with a young volunteer from the UK, Malika did community work addressing social injustice and climate change - although he'd never heard of the latter when he started the role.

"That opportunity really made a big difference in my career," Malika recalls.

There was a lot of competition for the position with the British Council, but Malika was selected, passionate and motivated by what he had seen working casual jobs up to that point in his life.

Although he qualified to attend college at 18, Malika couldn’t afford the tuition fees, and, like most Kenyan men, he turned to casual labour. That meant getting up early in the morning and hitting the streets to look for a job. Any job.

Most jobs are for a day or maybe two, occasionally a week or longer. What you get is a matter of luck, but it won't provide security or a stable income, that's for sure.

That's tough, yet not as tough as seeing young girls, sometimes only 12, doing the same and being asked to perform sexual favours to be given work, Malika says, upset evident in his voice. Witnessing that kind of social injustice turned him into a writer. Malika wanted to raise awareness of the unfair treatment of women and started reporting alongside his day job.

Malika can't now recall how many articles he submitted to the big newspapers in his country. For years, they never replied or published anything he wrote.

But one day in 2017, while searching the internet, Malika noticed an organisation called Wellbeing of Women based in the UK. He sent them an article he wrote about schoolgirls in Kenya undergoing unsafe abortions, and, to his surprise, they replied. Wellbeing of Women accepted the piece – and Malika got his first publication. The article was published in the UK initially but went on to get global coverage when a US think-tank picked it up too.

That was a great achievement, yet not his proudest work.

Malika's proudest work is an article about how the simple act of giving girls bicycles to get to school can change lives. The story provides a glimpse into the life of Carol, a 15-year-old secondary school student who would have had to drop out of school if it hadn't been for her bicycle. Outside of school, Carol cooked and cleaned for her family, just like most Kenyan girls, and riding a bike instead of walking to school saved so much time that she could finish her education.

That article was published in mainstream newspapers in 16 African countries and the US, and during the 2019 World Economic Forum, the piece was featured on its website. It launched Malika's writing career.

He now regularly writes for the newspapers that ignored him before, but challenges remain when it comes to publishing serious stories. Malika says, "Media outlets like to publish hype and gossip, things that make the public excited," and those are not the topics he writes about, having moved towards science writing in the past two years.

Despite that shift, Malika continues to be passionate about human rights. In 2021, he founded One More Percent, a grassroots media company aiming to reshape the narratives of traditionally marginalised populations, including women, people living with disabilities, and gender minorities. Malika wants to amplify the voices that often go unheard, but to him, ultimately, success is enabling those people to tell their own stories, using their own voices.

Edited by Melyka Bennett

HennyGe Wichers specialised in writing features and news pieces on Science & Technology. She has a particular interest in emerging technologies and their impact on society. After completing her doctorate in Economics, she worked in Big Tech and Innovation before turning to freelance writing.

The Early Career Science Writer Network (ECSWN) is a global community of science media professionals within the first five years of a journalism career. The network offers training and development opportunities for its members and provides an informal space to chat openly with peers at the same level.

The ‘A Day in the Life of’ (ADITLO) series is a collection of profile-type articles chronicling a day in the life of different media roles, written by members of the ECSWN. The scheme provides a valuable opportunity for new journalists to develop interviewing, writing and editing skills while creating a helpful resource which gives those joining the industry an insight into the everyday reality of different science journalism roles.

'A Day in the Life of Laura Lansdowne, Managing Editor at Technology Networks'. By Amarachi Orie